The content of this website is no longer being updated. For information on current assessment activities, please visit http://www.globalchange.gov/what-we-do/assessment

Southwest

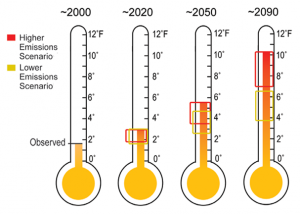

Observed and Projected Temperature Rise The average temperature in the Southwest has already increased roughly 1.5°F compared to a 1960-1979 baseline period. By the end of the century, average annual temperature is projected to rise approximately 4°F to 10°F above the historical baseline, averaged over the Southwest region. The brackets on the thermometers represent the likely range of model projections, though lower or higher outcomes are possible. Image Reference: CMIP3-A1The Southwest region stretches from the southern Rocky Mountains to the Pacific Coast. Elevations range from the lowest in the country to among the highest, with climates ranging from the driest to some of the wettest. Past climate records based on changes in Colorado River flows indicate that drought is a frequent feature of the Southwest, with some of the longest documented “megadroughts” on Earth. Since the 1940s, the region has experienced its most rapid population and urban growth. During this time, there were both unusually wet periods (including much of 1980s and 1990s) and dry periods (including much of 1950s and 1960s).2 The prospect of future droughts becoming more severe as a result of global warming is a significant concern, especially because the Southwest continues to lead the nation in population growth.

The average temperature in the Southwest has already increased roughly 1.5°F compared to a 1960-1979 baseline period. By the end of the century, average annual temperature is projected to rise approximately 4°F to 10°F above the historical baseline, averaged over the Southwest region. The brackets on the thermometers represent the likely range of model projections, though lower or higher outcomes are possible. Image Reference: CMIP3-A1The Southwest region stretches from the southern Rocky Mountains to the Pacific Coast. Elevations range from the lowest in the country to among the highest, with climates ranging from the driest to some of the wettest. Past climate records based on changes in Colorado River flows indicate that drought is a frequent feature of the Southwest, with some of the longest documented “megadroughts” on Earth. Since the 1940s, the region has experienced its most rapid population and urban growth. During this time, there were both unusually wet periods (including much of 1980s and 1990s) and dry periods (including much of 1950s and 1960s).2 The prospect of future droughts becoming more severe as a result of global warming is a significant concern, especially because the Southwest continues to lead the nation in population growth.

Human-induced climate change appears to be well underway in the Southwest. Recent warming is among the most rapid in the nation, significantly more than the global average in some areas. This is driving declines in spring snowpack and Colorado River flow.3,4,5 Projections suggest continued strong warming, with much larger increases under higher emissions scenarios6 compared to lower emissions scenarios. Projected summertime temperature increases are greater than the annual average increases in some parts of the region, and are likely to be exacerbated locally by expanding urban heat island effects.7 Further water cycle changes are projected, which, combined with increasing temperatures, signal a serious water supply challenge in the decades and centuries ahead.3,8

Water Resources

Water supplies are projected to become increasingly scarce, calling for trade-offs among competing uses, and potentially leading to conflict.

Water is, quite literally, the lifeblood of the Southwest. The largest use of water in the region is associated with agriculture, including some of the nation’s most important crop-producing areas in California. Water is also an important source of hydroelectric power, and water is required for the large population growth in the region, particularly that of major cities such as Phoenix and Las Vegas. Water also plays a critical role in supporting healthy ecosystems across the region, both on land and in rivers and lakes.

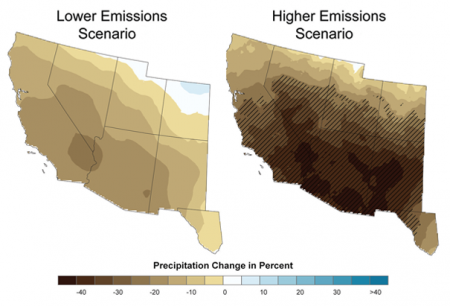

Projected Change in Spring Precipitation, 2080-2099 Percentage change in March-April-May precipitation for 2080-2099 compared to 1961-1979 for a lower emissions scenario6 (left) and a higher emissions scenario6 (right). Confidence in the projected changes is highest in the hatched areas. Image Reference: CMIP3-B9Water supplies in some areas of the Southwest are already becoming limited, and this trend toward scarcity is likely to be a harbinger of future water shortages.3,10 Groundwater pumping is lowering water tables, while rising temperatures reduce river flows in vital rivers including the Colorado.3 Limitations imposed on water supply by projected temperature increases are likely to be made worse by substantial reductions in rain and snowfall in the spring months, when precipitation is most needed to fill reservoirs to meet summer demand.11

Percentage change in March-April-May precipitation for 2080-2099 compared to 1961-1979 for a lower emissions scenario6 (left) and a higher emissions scenario6 (right). Confidence in the projected changes is highest in the hatched areas. Image Reference: CMIP3-B9Water supplies in some areas of the Southwest are already becoming limited, and this trend toward scarcity is likely to be a harbinger of future water shortages.3,10 Groundwater pumping is lowering water tables, while rising temperatures reduce river flows in vital rivers including the Colorado.3 Limitations imposed on water supply by projected temperature increases are likely to be made worse by substantial reductions in rain and snowfall in the spring months, when precipitation is most needed to fill reservoirs to meet summer demand.11

A warmer and drier future means extra care will be needed in planning the allocation of water for the coming decades. The Colorado Compact, negotiated in the 1920s, allocated the Colorado River’s water among the seven basin states. It was based, however, on unrealistic assumptions about how much water was available because the observations of runoff during the early 1900s turned out to be part of the greatest and longest high-flow period of the last five centuries.12 Today, even in normal decades, the Colorado River does not have enough water to meet the agreed-upon allocations. During droughts and under projected future conditions, the situation looks even bleaker.

During droughts, water designated for agriculture could provide a temporary back-up supply for urban water needs. Similarly, non-renewable groundwater could be tapped during especially dry periods. Both of these options, however, come at the cost of either current or future agricultural production.

Future of Drought in the Southwest

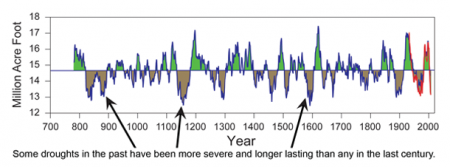

Droughts are a long-standing feature of the Southwest’s climate. The droughts of the last 110 years pale in comparison to some of the decades-long “megadroughts” that the region has experienced over the last 2000 years.13 During the closing decades of the 1500s, for example, major droughts gripped parts of the Southwest.14 These droughts sharply reduced the flow of the Colorado River12,15 and the all-important Sierra Nevada headwaters for California,16 and dried out the region as a whole. As of 2009, much of the Southwest remains in a drought that began around 1999. This event is the most severe western drought of the last 110 years, and is being exacerbated by record warming.17

Southwest: Drought Timeline Colorado River flow has been reconstructed back over 1200 years based primarily on tree-ring data. These data reveal that some droughts in the past have been more severe and longer lasting than any experienced in the last 100 years. The red line indicates actual measurements of river flow during the last 100 years. Models indicate that, in the future, droughts will continue to occur, but will become hotter, and thus more severe, over time.18 Image Source: after Meko et al.15Over this century, projections point to an increasing probability of drought for the region.18,19 Many aspects of these projections, including a northward shift in winter and spring storm tracks, are consistent with observed trends over recent decades.20,21,22 Thus, the most likely future for the Southwest is a substantially drier one (although there is presently no consensus on how the region's summer monsoon [rainy season] might change in the future). Combined with the historical record of severe droughts and the current uncertainty regarding the exact causes and drivers of these past events, the Southwest must be prepared for droughts that could potentially result from multiple causes. The combined effects of natural climate variability and human-induced climate change could turn out to be a devastating “one-two punch” for the region.

Colorado River flow has been reconstructed back over 1200 years based primarily on tree-ring data. These data reveal that some droughts in the past have been more severe and longer lasting than any experienced in the last 100 years. The red line indicates actual measurements of river flow during the last 100 years. Models indicate that, in the future, droughts will continue to occur, but will become hotter, and thus more severe, over time.18 Image Source: after Meko et al.15Over this century, projections point to an increasing probability of drought for the region.18,19 Many aspects of these projections, including a northward shift in winter and spring storm tracks, are consistent with observed trends over recent decades.20,21,22 Thus, the most likely future for the Southwest is a substantially drier one (although there is presently no consensus on how the region's summer monsoon [rainy season] might change in the future). Combined with the historical record of severe droughts and the current uncertainty regarding the exact causes and drivers of these past events, the Southwest must be prepared for droughts that could potentially result from multiple causes. The combined effects of natural climate variability and human-induced climate change could turn out to be a devastating “one-two punch” for the region.

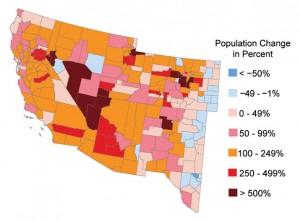

Change in Population from 1970 to 2008 - Southwest The map above of percentage changes in county population between 1970 and 2008 shows that the Southwest has experienced very rapid growth in recent decades (indicated in orange, red, and maroon). Image Reference: U.S. Census23Water is already a subject of contention in the Southwest, and climate change – coupled with rapid population growth – promises to increase the likelihood of water-related conflict. Projected temperature increases, combined with river-flow reductions, will increase the risk of water conflicts between sectors, states, and even nations. In recent years, negotiations regarding existing water supplies have taken place among the seven states sharing the Colorado River and the two states (New Mexico and Texas) sharing the Rio Grande. Mexico and the United States already disagree on meeting their treaty allocations of Rio Grande and Colorado River water.

The map above of percentage changes in county population between 1970 and 2008 shows that the Southwest has experienced very rapid growth in recent decades (indicated in orange, red, and maroon). Image Reference: U.S. Census23Water is already a subject of contention in the Southwest, and climate change – coupled with rapid population growth – promises to increase the likelihood of water-related conflict. Projected temperature increases, combined with river-flow reductions, will increase the risk of water conflicts between sectors, states, and even nations. In recent years, negotiations regarding existing water supplies have taken place among the seven states sharing the Colorado River and the two states (New Mexico and Texas) sharing the Rio Grande. Mexico and the United States already disagree on meeting their treaty allocations of Rio Grande and Colorado River water.

In addition, many water settlements between the U.S. Government and Native American tribes have yet to be fully worked out. The Southwest is home to dozens of Native communities whose status as sovereign nations means they hold rights to the water for use on their land. However, the amount of water actually available to each nation is determined through negotiations and litigation. Increasing water demand in the Southwest is driving current negotiations and litigation of tribal water rights. While several nations have legally settled their water rights, many other tribal negotiations are either currently underway or pending. Competing demands from treaty rights, rapid development, and changes in agriculture in the region, exacerbated by years of drought and climate change, have the potential to spark significant conflict over an already over-allocated and dwindling resource.

Landscape Transformation

Increasing temperature, drought, wildfire, and invasive species will accelerate transformation of the landscape.

Climate change already appears to be influencing both natural and managed ecosystems of the Southwest.17,24 Future landscape impacts are likely to be substantial, threatening biodiversity, protected areas, and ranching and agricultural lands. These changes are often driven by multiple factors, including changes in temperature and drought patterns, wildfire, invasive species, and pests.

Conditions observed in recent years can serve as indicators for future change. For example, temperature increases have made the current drought in the region more severe than the natural droughts of the last several centuries. As a result, about 4,600 square miles of piñon-juniper woodland in the Four Corners region of the Southwest have experienced substantial die-off of piñon pine trees.17 Record wildfires are also being driven by rising temperatures and related reductions in spring snowpack and soil moisture.24

How climate change will affect fire in the Southwest varies according to location. In general, total area burned is projected to increase.25 How this plays out at individual locations, however, depends on regional changes in temperature and precipitation, as well as on whether fire in the area is currently limited by fuel availability or by rainfall.26 For example, fires in wetter, forested areas are expected to increase in frequency, while areas where fire is limited by the availability of fine fuels experience decreases.26 Climate changes could also create subtle shifts in fire behavior, allowing more “runaway fires” – fires that are thought to have been brought under control, but then rekindle.27 The magnitude of fire damages, in terms of economic impacts as well as direct endangerment, also increases as urban development increasingly impinges on forested areas.26,28

Climate-fire dynamics will also be affected by changes in the distribution of ecosystems across the Southwest. Increasing temperatures and shifting precipitation patterns will drive declines in high-elevation ecosystems such as alpine forests and tundra.25,29 Under higher emissions scenarios,6 high-elevation forests in California, for example, are projected to decline by 60 to 90 percent before the end of the century.30,25 At the same time, grasslands are projected to expand, another factor likely to increase fire risk.

As temperatures rise, some iconic landscapes of the Southwest will be greatly altered as species shift their ranges northward and upward to cooler climates, and fires attack unaccustomed ecosystems which lack natural defenses. The Sonoran Desert, for example, famous for the saguaro cactus, would look very different if more woody species spread northward from Mexico into areas currently dominated by succulents (such as cacti) or native grasses.31 The desert is already being invaded by red brome and buffle grasses that do well in high temperatures and are native to Africa and the Mediterranean. Not only do these noxious weeds out-compete some native species in the Sonoran Desert, they also fuel hot, cactus-killing fires. With these invasive plant species and climate change, the Saguaro and Joshua Tree national parks could end up with far fewer of their namesake plants.32 In California, two-thirds of the more than 5,500 native plant species are projected to experience range reductions up to 80 percent before the end of this century under projected warming.33 In their search for optimal conditions, some species will move uphill, others northward, breaking up present-day ecosystems; those species moving southward to higher elevations might cut off future migration options as temperatures continue to increase.

The potential for successful plant and animal adaptation to coming change is further hampered by existing regional threats such as human-caused fragmentation of the landscape, invasive species, river-flow reductions, and pollution. Given the mountainous nature of the Southwest, and the associated impediments to species shifting their ranges, climate change likely places other species at risk. Some areas have already been identified as possible refuges where species at risk could continue to live if these areas were preserved for this purpose.33 Other rapidly changing landscapes will require major adjustments, not only from plant and animal species, but also by the region’s ranchers, foresters, and other inhabitants.

Flooding

Increased frequency and altered timing of flooding will increase risks to people, ecosystems, and infrastructure.

A Biodiversity Hotspot

The Southwest is home to two of the world’s 34 designated “biodiversity hotspots.” These at-risk regions have two special qualities: they hold unusually large numbers of plant and animal species that are endemic (found nowhere else), and they have already lost over 70 percent of their native vegetation.34,35 About half the world’s species of plants and land animals occur only in these 34 locations, though they cover just 2.3 percent of the Earth’s land surface.

One of these biodiversity hotspots is the Madrean Pine-Oak Woodlands. Once covering 178 square miles, only isolated patches remain in the United States, mainly on mountaintops in southern Arizona, New Mexico, and West Texas. The greatest diversity of pine species in the world grows in this area: 44 of the 110 varieties,36 as well as more than 150 species of oak.37 Some 5,300 to 6,700 flowering plant species inhabit the ecosystem, and over 500 bird species, 23 of which are endemic. More hummingbirds are found here than anywhere else in the United States. There are 384 species of reptiles, 37 of which are endemic, and 328 species of mammals, six of which are endemic. There are 84 fish species, 18 of which are endemic. Some 200 species of butterfly thrive here, of which 45 are endemic, including the Monarch that migrates 2,500 miles north to Canada each year.38 Ecotourism has become the economic driver in many parts of this region, but logging, land clearing for agriculture, urban development, and now climate change threaten the region’s viability.

Paradoxically, a warmer atmosphere and an intensified water cycle are likely to mean not only a greater likelihood of drought for the Southwest, but also an increased risk of flooding. Winter precipitation in Arizona, for example, is already becoming more variable, with a trend toward both more frequent extremely dry and extremely wet winters.39 Some water systems rely on smaller reservoirs being filled up each year. More frequent dry winters suggest an increased risk of these systems running short of water. However, a greater potential for flooding also means reservoirs cannot be filled to capacity as safely in years where that is possible. Flooding also causes reservoirs to fill with sediment at a faster rate, thus reducing their water-storage capacities.

On the global and national scales, precipitation patterns are already observed to be shifting, with more rain falling in heavy downpours that can lead to flooding.18,40 Rapid landscape transformation due to vegetation die-off and wildfire as well as loss of wetlands along rivers is also likely to reduce flood-buffering capacity. Moreover, increased flood risk in the Southwest is likely to result from a combination of decreased snow cover on the lower slopes of high mountains, and an increased fraction of winter precipitation falling as rain and therefore running off more rapidly.41 The increase in rain on snow events will also result in rapid runoff and flooding.42

The most obvious impact of more frequent flooding is a greater risk to human beings and their infrastructure. This applies to locations along major rivers, but also to much broader and highly vulnerable areas such as the Sacramento–San Joaquin River Delta system. Stretching from the San Francisco Bay nearly to the state capital of Sacramento, the Sacramento–San Joaquin River Delta and Suisun Marsh make up the largest estuary on the West Coast of North America. With its rich soils and rapid subsidence rates – in some locations as high as 2 or more feet per decade – the entire Delta region is now below sea level, protected by more than a thousand miles of levees and dams.43 Projected changes in the timing and amount of river flow, particularly in winter and spring, is estimated to more than double the risk of Delta flooding events by mid-century, and result in an eight-fold increase before the end of the century.44 Taking into account the additional risk of a major seismic event and increases in sea level due to climate change over this century, the California Bay–Delta Authority has concluded that the Delta and Suisun Marsh are not sustainable under current practices; efforts are underway to identify and implement adaptation strategies aimed at reducing these risks.44

Tourism and Recreation

Unique tourism and recreation opportunities are likely to suffer.

Tourism and recreation are important aspects of the region’s economy. Increasing temperatures will affect important winter activities such as downhill and cross-country skiing, snowshoeing, and snowmobiling, which require snow on the ground. Projections indicate later snow and less snow coverage in ski resort areas, particularly those at lower elevations and in the southern part of the region.30 Decreases from 40 to almost 90 percent are likely in end-of-season snowpack under a higher emissions scenario6 in counties with major ski resorts from New Mexico to California.45 In addition to shorter seasons, earlier wet snow avalanches – more than six weeks earlier by the end of this century under a higher emissions scenario6 – could force ski areas to shut down affected runs before the season would otherwise end.46 Resorts require a certain number of days just to break even; cutting the season short by even a few weeks, particularly if those occur during the lucrative holiday season, could easily render a resort unprofitable.

Even in non-winter months, ecosystem degradation will affect the quality of the experience for hikers, bikers, birders, and others who enjoy the Southwest’s natural beauty. Water sports that depend on the flows of rivers and sufficient water in lakes and reservoirs are already being affected, and much larger changes are expected.

Rising Temperatures

Cities and agriculture face increasing risks from a changing climate.

Resource use in the Southwest is involved in a constant three-way tug-of-war among preserving natural ecosystems, supplying the needs of rapidly expanding urban areas, and protecting the lucrative agricultural sector, which, particularly in California, is largely based on highly temperature- and water-sensitive specialty crops. Urban areas are also sensitive to temperature-related impacts on air quality, electricity demand, and the health of their inhabitants.

The magnitude of projected temperature increases for the Southwest, particularly when combined with urban heat island effects for major cities such as Phoenix, Albuquerque, Las Vegas, and many California cities, represent significant stresses to health, electricity, and water supply in a region that already experiences very high summer temperatures.30,47,7

If present-day levels of ozone-producing emissions are maintained, rising temperatures also imply declining air quality in urban areas such as those in California which already experience some of the worst air quality in the nation (see Society sector).48 Continued rapid population growth is expected to exacerbate these concerns.

With more intense, longer-lasting heat wave events projected to occur over this century, demands for air conditioning are expected to deplete electricity supplies, increasing risks of brownouts and blackouts.47 Electricity supplies will also be affected by changes in the timing of river flows and where hydroelectric systems have limited storage capacity and reservoirs (see Energy sector).49,50

Much of the region's agriculture will experience detrimental impacts in a warmer future, particularly specialty crops in California such as apricots, almonds, artichokes, figs, kiwis, olives, and walnuts.51,52 These and other specialty crops require a minimum number of hours at a chilling temperature threshold in the winter to become dormant and set fruit for the following year.51 Accumulated winter chilling hours have already decreased across central California and its coastal valleys. This trend is projected to continue to the point where chilling thresholds for many key crops would no longer be met. A steady reduction in winter chilling could have serious economic impacts on fruit and nut production in the region. California’s losses due to future climate change are estimated between zero and 40 percent for wine and table grapes, almonds, oranges, walnuts, and avocadoes, varying significantly by location.52

Adaptation strategies for agriculture in California include more efficient irrigation and shifts in cropping patterns, which have the potential to help compensate for climate-driven increases in water demand for agriculture due to rising temperatures.53 The ability to use groundwater and/or water designated for agriculture as backup supplies for urban uses in times of severe drought is expected to become more important in the future as climate change dries out the Southwest; however, these supplies are at risk of being depleted as urban populations swell (see Water sector).

Adaptation: Strategies for Fire

Living with present-day levels of fire risk, along with projected increases in risk, involves actions by residents along the urban-forest interface as well as fire and land management officials. Some basic strategies for reducing damage to structures due to fires are being encouraged by groups like National Firewise Communities, an interagency program that encourages wildfire preparedness measures such as creating defensible space around residential structures by thinning trees and brush, choosing fire-resistant plants, selecting ignition-resistant building materials and design features, positioning structures away from slopes, and working with firefighters to develop emergency plans.

Additional strategies for responding to the increased risk of fire as climate continues to change could include adding firefighting resources27 and improving evacuation procedures and communications infrastructure. Also important would be regularly updated insights into what the latest climate science implies for changes in types, locations, timing, and potential severity of fire risks over seasons to decades and beyond; implications for related political, legal, economic, and social institutions; and improving predictions for regeneration of burnt-over areas and the implications for subsequent fire risks. Reconsideration of policies that encourage growth of residential developments in or near forests is another potential avenue for adaptive strategies.28

References

- 1. [93] various. footnote 93., 2009.

- 2. [449] Center, NOAA's National Climatic Data. Southwest Region Palmer Hydrological Drought Index (PHDI) In Climate of 2008 - October: Southwest Region Moisture Status. Asheville, NC: NOAA National Climatic Data Center, 2008.

- 3. a. b. c. d. [34] Barnett, T. P., D. W. Pierce, H. G. Hidalgo, C. Bonfils, B. D. Santer, T. Das, G. Bala, A. W. Wood, T. Nozawa, A. A. Mirin et al. "Human-induced changes in the hydrology of the western United States." Science 319, no. 5866 (2008): 1080-1083.

- 4. [160] Pierce, D. W., T. P. Barnett, H. G. Hidalgo, T. Das, C. Bonfils, B. D. Santer, G. Bala, M. D. Dettinger, D. R. Cayan, A. Mirin et al. "Attribution of Declining Western U.S. Snowpack to Human Effects." Journal of Climate 21, no. 23 (2008): 6425-6444.

- 5. [161] Bonfils, C., B. D. Santer, D. W. Pierce, H. G. Hidalgo, G. Bala, T. Das, T. P. Barnett, D. R. Cayan, C. Doutriaux, A. W. Wood et al. "Detection and Attribution of Temperature Changes in the Mountainous Western United States." Journal of Climate 21, no. 23 (2008): 6404-6424.

- 6. a. b. c. d. e. f. [91] various. footnote 91., 2009.

- 7. a. b. [450] Guhathakurta, S., and P. Gober. "The Impact of the Phoenix Urban Heat Island on Residential Water Use." Journal of the American Planning Association 73, no. 3 (2007): 317-329.

- 8. [159] Rauscher, S. A., J. S. Pal, N. S. Diffenbaugh, and M. M. Benedetti. "Future Changes in Snowmelt-driven Runoff Timing over the Western United States." Geophysical Research Letters 35 (2008): -.

- 9. [117] various. footnote 117., 2009.

- 10. [451] Gleick, P. H.. "Regional Hydrologic Consequences of Increases in Atmospheric CO2 and Other Trace Gases." Climatic Change 10, no. 2 (1987): 137-160.

- 11. [151] Milly, P. C. D., J. Betancourt, M. Falkenmark, R. M. Hirsch, Z. W. Kundzewicz, D. P. Lettenmaier, and R. J. Stouffer. "Stationarity Is Dead: Whither Water Management?" Science 319, no. 5863 (2008): 573-574.

- 12. a. b. [452] Woodhouse, CA, S. T. Gray, and D. M. Meko. "Updated Streamflow Reconstructions for the Upper Colorado River Basin." Water Resources Research 42 (2006).

- 13. [419] Woodhouse, CA, and J. T. Overpeck. "2000 Years of Drought Variability in the Central United States." Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society 79, no. 12 (1998): 2693-2714.

- 14. [189] Cook, E. R., CA Woodhouse, C. M. Eakin, D. M. Meko, and D. W. Stahle. "Long-term Aridity Changes in the Western United States." Science 306, no. 5698 (2004): 1015-1018.

- 15. a. b. [453] Meko, D. M., CA Woodhouse, C. A. Baisan, T. Knight, J. J. Lukas, M. K. Hughes, and M. W. Salzer. "Medieval Drought in the Upper Colorado River Basin." Geophysical Research Letters 34 (2007): -.

- 16. [454] Stine, S.. "Extreme and Persistent Drought in California and Patagonia during Mediaeval Time." Nature 369, no. 6481 (1994): 546-549.

- 17. a. b. c. [455] Breshears, D. D., N. S. Cobb, P. M. Rich, K. P. Price, C. D. Allen, R. G. Balice, W. H. Romme, J. H. Kastens, M. L. Floyd, J. Belnap et al. "Regional Vegetation Die-off in Response to Global-change-type Drought." Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 102, no. 42 (2005): 15144-15148.

- 18. a. b. c. [90] Meehl, G. A., T. F. Stocker, W. D. Collins, P. Friedlingstein, A. T. Gaye, JM Gregory, A. Kitoh, R. Knutti, J. M. Murphy, A. Noda et al. "Global Climate Projections." In Climate Change 2007: The Physical Basis, edited by S. Solomon, D. Qin, M. Manning, Z. Chen, M. Marquis, K. B. Averyt, M. Tignor and H. L. Miller, 747-845. Vol. Contribution of Working Group I to the Fourth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Cambridge, UK and New York, NY: Cambridge University Press, 2007.

- 19. [115] Seager, R., M. Ting, I. Held, Y. Kushnir, J. Lu, G. Vecchi, H. - P. Huang, N. Harnik, A. Leetmaa, N. - C. Lau et al. "Model Projections of an Imminent Transition to a More Arid Climate in Southwestern North America." Science 316, no. 5828 (2007): 1181-1184.

- 20. [96] Seidel, D. J., Q. Fu, W. J. Randel, and T. J. Reichler. "Widening of the Tropical Belt in a Changing Climate." Nature Geoscience 1, no. 1 (2008): 21-24.

- 21. [456] Archer, C. L., and K. Caldeira. "Historical Trends in the Jet Streams." Geophysical Research Letters 35 (2008).

- 22. [457] McAfee, S. A., and J. L. Russell. "Northern Annular Mode Impact on Spring Climate in the Western United States." Geophysical Research Letters 35 (2008): -.

- 23. [207] Bureau, Census U. S.. Population of States and Counties of the United States: 1790-2000. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Census Bureau, 2002.

- 24. a. b. [294] Westerling, A. L., H. G. Hidalgo, D. R. Cayan, and T. W. Swetnam. "Warming and Earlier Spring Increase Western U.S. Forest Wildfire Activity." Science 313, no. 5789 (2006): 940-943.

- 25. a. b. c. [459] Lenihan, J. M., D. Bachelet, R. P. Neilson, and R. Drapek. "Response of Vegetation Distribution, Ecosystem Productivity, and Fire to Climate Change Scenarios for California." Climatic Change 87, no. Supplement 1 (2008): S215-S230.

- 26. a. b. c. [460] Westerling, A. L., and B. P. Bryant. "Climate Change and Wildfire in California." Climatic Change 87, no. Supplement 1 (2008): S231-S249.

- 27. a. b. [461] Fried, J. S., J. K. Gilless, W. J. Riley, T. J. Moody, C. S. de Blas, K. Hayhoe, M. Moritz, S. Stephens, and M. Torn. "Predicting the Effect of Climate Change on Wildfire Behavior and Initial Attack Success." Climatic Change 87, no. Supplement 1 (2008): S251-S264.

- 28. a. b. [462] Moritz, M. A., and S. L. Stephens. "Fire and Sustainability: Considerations for California's Altered Future Climate." Climatic Change 87, no. Supplement 1 (2008): S265-S271.

- 29. [463] Rehfeldt, G. E., N. L. Crookston, M. V. Warwell, and J. S. Evans. "Empirical Analyses of Plant-Climate Relationships for the Western United States." International Journal of Plant Sciences 167, no. 6 (2006): 1123-1150.

- 30. a. b. c. [284] Hayhoe, K., D. Cayan, CB Field, P. C. Frumhoff, E. P. Maurer, N. L. Miller, S. C. Moser, S. H. Schneider, K. N. Cahill, E. E. Cleland et al. "Emissions Pathways, Climate Change, and Impacts on California." Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 101, no. 34 (2004): 12422-12427.

- 31. [464] Weiss, J. L., and J. T. Overpeck. "Is the Sonoran Desert Losing its Cool?" Global Change Biology 11, no. 12 (2005): 2065-2077.

- 32. [465] Dole, K. P., M. E. Loik, and L. C. Sloan. "The Relative Importance of Climate Change and the Physiological Effects of CO2 on Freezing Tolerance for the Future Distribution of Yucca brevifolia." Global and Planetary Change 36, no. 1-2 (2003): 137-146.

- 33. a. b. [466] Loarie, S. R., B. E. Carter, K. Hayhoe, S. McMahon, R. Moe, C. A. Knight, and D. D. Ackerly. "Climate Change and the Future of California's Endemic Flora." PLoS ONE 3, no. 6 (2008): e2502.

- 34. [467] Myers, N., R. A. Mittermeier, C. G. Mittermeier, G. A. B. da Fonseca, and J. Kent. "Biodiversity Hotspots for Conservation Priorities." Nature 403, no. 6772 (2000): 853-858.

- 35. [468] Mittermeier, R. A., P. Robles Gil, M. Hoffman, J. Pilgrim, T. Brooks, C. G. Mittermeier, J. Lamoreux, and G. A. B. da Fonseca. Hotspots Revisited: Earth's Biologically Richest and Most Endangered Terrestrial Ecoregions. Vol. 4. Washington, D.C.: Conservation International, 2005.

- 36. [469] Farjon, A., C. N. Page, and IUCN/SSC Conifer Specialist Group. Conifers: Status Survey and Conservation Action Plan. Gland, Switzerland, and Cambridge, UK: International Union for Conservation of Nature, 1999.

- 37. [470] Nixon, K. C.. "The Genus Quercus in Mexico." In Biological Diversity of Mexico: Origins and Distribution, edited by T. P. Ramamoorthy, R. Bye, A. Lot and J. Fa, 812 pp. New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 1993.

- 38. [471] Brower, L. P., G. Castilleja, A. Peralta, J. Lopez-Garcia, L. Bojorquez-Tapia, S. Diaz, D. Melgarejo, and M. Missrie. "Quantitative Changes in Forest Quality in a Principal Overwintering Area of the Monarch Butterfly in Mexico, 1971-1999." Conservation Biology 16, no. 2 (2002): 346-359.

- 39. [472] Goodrich, G. B., and A. W. Ellis. "Climatic Controls and Hydrologic Impacts of a Recent Extreme Seasonal Precipitation Reversal in Arizona." Journal of Applied Meteorology and Climatology 47, no. 2 (2008): 498-508.

- 40. [473] Allan, R. P., and B. J. Soden. "Atmospheric Warming and the Amplification of Precipitation Extremes." Science 321, no. 5895 (2008): 1481-1484.

- 41. [154] Knowles, N., M. D. Dettinger, and D. R. Cayan. "Trends in Snowfall Versus Rainfall in the Western United States." Journal of Climate 19, no. 18 (2006): 4545-4559.

- 42. [474] Bales, R. C., N. P. Molotch, T. H. Painter, M. D. Dettinger, R. Rice, and J. Dozier. "Mountain Hydrology of the Western United States." Water Resources Research 42 (2006).

- 43. [475] "Delta Risk Management Strategy - Section 2: Sacramento/San Joaquin Delta and Suisun Marsh." In Phase 1 Report: Risk Analysis, 13 pp. California Department of Water Resources, 2008.

- 44. a. b. [476] "Delta Risk Management Strategy - Summary Report." In Phase I Report: Risk Analysis, 42 pp. California Department of Water Resources, 2008.

- 45. [477] Zimmerman, G. P., C. O'Brady, and B. Hurlbutt. "Climate Change: Modeling a Warmer Rockies and Assessing the Implications." In The 2006 State of the Rockies Report Card, 89-102. Colorado Springs, CO: Colorado College, 2006.

- 46. [478] Lazar, B., and M. Williams. "Climate Change in Western Ski Areas: Potential Changes in the Timing of Wet Avalanches and Snow Quality for the Aspen Ski Area in the Years 2030 and 2100." Cold Regions Science and Technology 51, no. 2-3 (2008): 219-228.

- 47. a. b. [325] Miller, N. L., K. Hayhoe, J. Jin, and M. Auffhammer. "Climate, Extreme Heat, and Electricity Demand in California." Journal of Applied Meteorology and Climatology 47, no. 6 (2008): 1834-1844.

- 48. [479] Kleeman, M. J.. "A Preliminary Assessment of the Sensitivity of Air Quality in California to Global Change." Climatic Change 87, no. Supplement 1 (2008): S273-S292.

- 49. [480] Vicuna, S., R. Leonardson, M. W. Hanemann, L. L. Dale, and J. A. Dracup. "Climate Change Impacts on High Elevation Hydropower Generation in California's Sierra Nevada: A Case Study in the Upper American River." Climatic Change 87, no. Supplement 1 (2008): S123-S137.

- 50. [481] Medellin-Azuara, J., J. J. Harou, M. A. Olivares, K. Madani, J. R. Lund, R. E. Howitt, S. K. Tanaka, M. W. Jenkins, and T. Zhu. "Adaptability and Adaptations of California's Water Supply System to Dry Climate Warming." Climatic Change 87, no. Supplement 1 (2008): S75-S90.

- 51. a. b. [482] Baldocchi, D., and S. Wong. "Accumulated Winter Chill is Decreasing in the Fruit Growing Regions of California." Climatic Change 87, no. Supplement 1 (2008): S153-S166.

- 52. a. b. [483] Lobell, D., C. Field, K. Cahill, and C. Bonfils. "Impacts of Future Climate Change on California Perennial Crop Yields: Model Projections with Climate and Crop Uncertainties." Agricultural and Forest Meteorology 141, no. 2-4 (2006): 208-218.

- 53. [484] Purkey, D. R., B. Joyce, S. Vicuna, M. W. Hanemann, L. L. Dale, D. Yates, and J. A. Dracup. "Robust Analysis of Future Climate Change Impacts on Water for Agriculture and Other Sectors: A Case Study in the Sacramento Valley." Climatic Change 87, no. Supplement 1 (2008): S109-S122.